Over the last couple winters, Sierra Streams Institute has begun conducting targeted stormwater monitoring as a part of our normal watershed monitoring regimen. In light of the some of the recent inclement weather we’ve experienced in the Sierra Foothills, our executive director Jeff Lauder wrote an article in January 2023 on the impact of atmospheric rivers on our local watershed (which you can read here), so in this article, we’ll further discuss the necessity of targeted stormwater monitoring with a focus on the environmental effects of turbidity.

Turbidity is a measure of how much light is scattered by suspended particles of solid matter in a solution. These particles can originate from natural processes such as decomposition of plant or animal material, but they also arise from human activities like construction, industrial discharges, soil erosion, road and agricultural runoff, and sewage. And in the presence of heavy precipitation, all of these sources of pollution become connected to our waterways.

Even visually, as all readers of this article will have likely experienced, one can observe the drastic effects that storm events have on the flow and appearance of a river (pictured below).

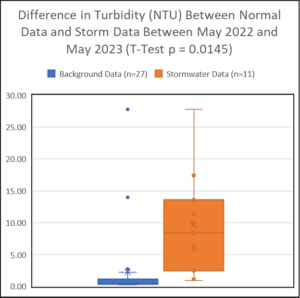

Taking a more quantitative look at the data (illustrated in the accompanying box plot), we find that there is a significant difference between the average turbidity in stormwater events as opposed to the readings seen throughout our normal water monitoring. This shows that stormwater monitoring gives us data that we would not otherwise capture, thereby giving us insight into the impacts of heavy precipitation on the watershed.

Despite the myriad substances that can find their way into a waterway during a storm, it is generally the case that simple sedimentation has the greatest environmental impact on our watershed. Sedimentation occurs when particles suspended in the water column settle out at the bottom of a stream or river bed. Over time, excess sedimentation can lead to the disruption of aquatic habitats and a change in the path of certain streams leading to wider shifts in habitat – e.g. a greater distance between riffles in the stream, leading to changes in how nutrients move through the aquatic environment.

In the 2006 State of Sierra Waters report by the Sierra Nevada Alliance, it was found that 14 of the 24 watersheds sampled (or 58%) had reaches affected by excess sedimentation. In the Yuba watershed this included reaches in: Bullards Bar, Camp Far West, Englebright, Little Deer Creek, Rollins Reservoir, Scotts Flat Reservoir, South Fork Yuba River above Edwards, and Combie Reservoir. Turbidity and suspended sediment are generally positively correlated, however, the degree of correlation is temporally and spatially dependent as non-sedimentary particles such as algae and ash also affect turbidity measurements.

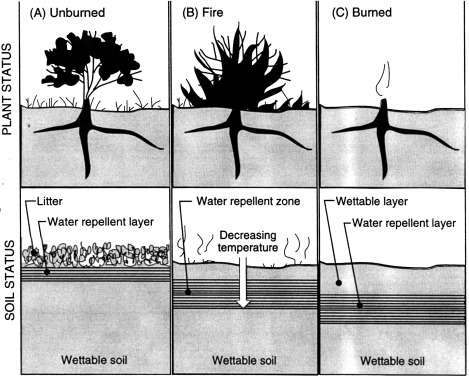

Figure depicting the impermeable hydrophobic soil layer that occurs when the soil surface is exposed to temperatures above 175C.

These effects are further exacerbated by severe wildfires, like those we’ve seen in recent years. When wildfires burn the soil surface, hydrophobic substances are created and move downward along a decreasing temperature gradient (illustrated above). High-severity wildfires create a water-repellent layer up to 8 inches deep, leaving the soil surface extremely vulnerable to erosion. Wildfires consume the organic material in the duff layer and the upper soil horizons, decreasing water holding capacity. This, in combination with the hydrophobic layer created in the soil, greatly increases the potential for erosion. (We’ll explore this topic further in a future blog post on post-fire water quality data.)

All of these particles in the water can then affect the population and diversity of the benthic macroinvertebrates that Sierra Streams studies as bioindicators of overall stream health, and you can read more about BMI population changes over time in the aforementioned article on atmospheric rivers.

As our climate shifts back towards its warm, El Niño phase, and our regional precipitation patterns shift in response, stormwater data collection will continue to be integral to understanding our ever-changing watershed.