There’s something in the water!

Hardly less charismatic than some gargantuan marine predator, Pectinatella magnifica or the “magnificent” bryozoan is a species of microscopic aquatic invertebrate – also known as a “moss animal” or zooid, usually less than a millimeter in size – that forms substantial, gelatinous colonies on submerged surfaces in freshwater drainages or bodies.

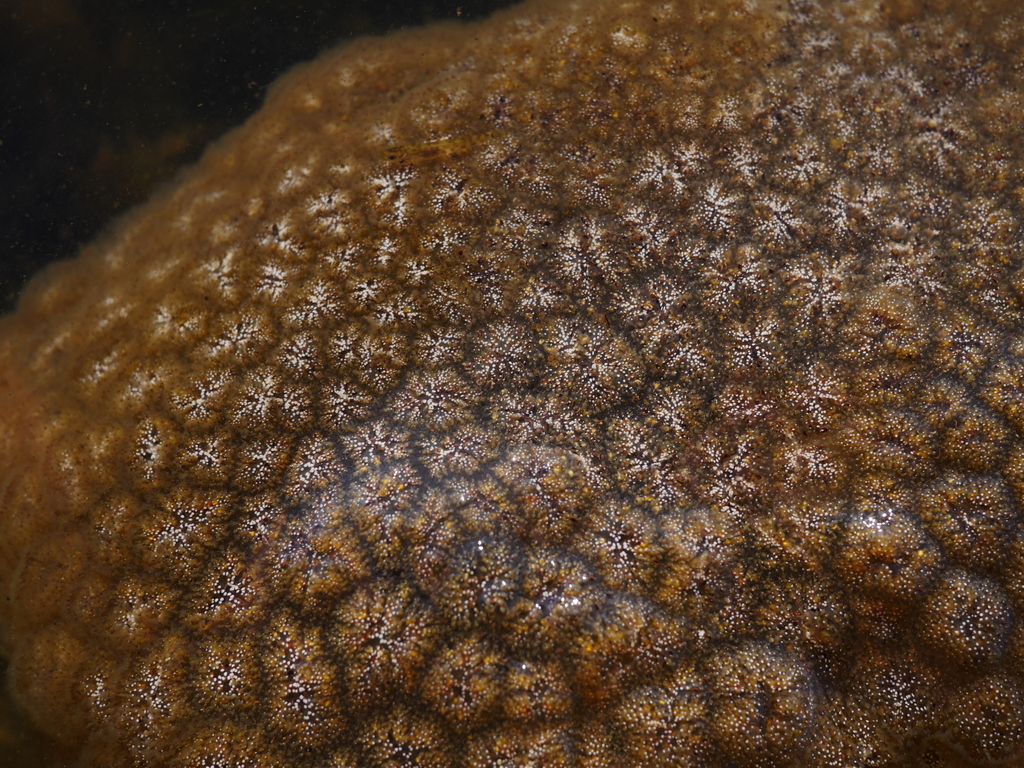

These blobs are comprised entirely of clones of the founding member that arrange themselves into a characteristic rosette-like pattern, whose every facet can contain upwards of a dozen individual organisms. Another key feature of bryozoans is their horseshoe-shaped appendage of ciliated tentacles, i.e. a lophophore, that allows them to filter out smaller organisms for its foodstuffs such as algae, bacteria, and protozoa. Incidentally, out of nearly 6000 known species of bryozoans, there are only about 50 known freshwater species of the class Phylactolaemata whose only extant order is Plumatellida, of which P. magnifica is an apparently thriving member.

Typically, the native distribution of the magnificent bryozoan spans throughout the Great Lakes region east of the Mississippi River, so here in California it is considered to be a nonindigenous species. According to the US Geological survey, it first reared its myriad heads in California back in 2013 and has continued to make appearances in the northern half of our state up to the present day.

By virtue of P. magnifica’s role as a filter feeder, the ecological implications of its presence in our watersheds are yet unclear. Most of the “lakes” in our region it would inhabit are themselves reservoirs that are more often than not populated by introduced species of fish, e.g. bass and trout, that could potentially prey on the bryozoans rather than be negatively affected by them.

Of course, the sheer biomass of these blobs, which can range from 1-2 feet in diameter, does raise implications for their effects on water quality and temperature by virtue of how much organic material they remove from the water versus how much they add to it simply by existing.

(Please refer to SSI’s Monitoring webpage where we further discuss the relationship between turbidity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen.)

The USGS maintains a fantastic online database of nonindigenous aquatic species found across the country, including a map of community-reported observations of each species. The database entry for P. magnifica is quite extensive and definitely worth a read in order to get a better glimpse into the life of this likely unfamiliar zooid.

To find out more about these creatures and to report personal observations of them, visit its database entry on nas.er.usgs.gov.

And if you do encounter a colony out in the field, feel free to send us a photo at info@sierrastreamsinstitute.org. Please include location!