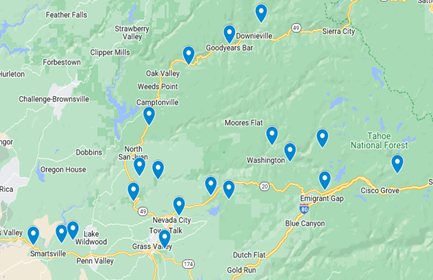

This summer, Sierra Streams Institute board member Dave Herbst worked with SSI staff, volunteers and recent graduates from UC Santa Cruz to pilot a project characterizing aquatic invertebrate biodiversity of streams throughout the Sierra Nevada, including the Yuba River. This work builds on our long-term citizen monitoring program, our partnership with the South Yuba River Citizens League, and incorporates the sophisticated DNA barcoding capabilities at UC Santa Cruz. In addition, it fills a gap in the major project now underway to catalog biodiversity among all life and habitats of the State of California (freshwater invertebrates are the one group not represented in that project). Read on for more information about the methods used in this study, as well as a firsthand account from one of the recent graduates!

DNA Barcoding, Explained

Libraries are repositories of information, knowledge, history and variety. So are watersheds. How do we catalog that biological repository?

Imagine a library full of books, but you don’t know what’s in there.

If you were able to tear one page out of each of those books it would be completely unique to that book, based on the sequence of words and letters found there. Given just the information from that one page of each book, you’d be able to reconstruct the contents of the entire library.

DNA barcoding is similar. If we want to know what species (books) are present in a stream or watershed (the library), we take a piece of tissue from each organism we find and extract the DNA. We then amplify the DNA so we have enough copies (of all the words in the book), then probe for just one gene sequence of DNA (the page) which codes for the mitochondrial gene (divergences in this gene are numerous enough that we can tell even closely related species apart).

Back to the library analogy: if the Dewey decimal system has a record of the book that our page is from, we can figure out which book the page belongs to. The same can be said of the Barcode of Life Database, or BOLD; we can figure out which organism has that particular genetic sequence for producing mitochondria. If BOLD doesn’t have that particular genetic sequence assigned to an organism, we can use that “page” to make a new record for the library catalog. If we do this for enough streams in a watershed, we start to make our own catalog that we can use to determine what lives in the whole watershed.

This genetic sequencing complements morphological taxonomy (what the organism looks like), which is like only being able to look at the cover of the book; it allows us to tell what’s inside the book as well. Combining the morphological taxonomy and information from the DNA, we can more accurately say what species exist in the stream and how distinct they may be from others with the same name or found in different locations.

DNA metabarcoding means that we look at mixed tissue or samples from many species combined together, comparing the barcodes to our library to determine what’s present. Metabarcoding tells you what is or is not there, but not the numerical abundance of what’s there, or exactly where in the environment it came from. Traditional BMI analysis identifies and counts each bug found, but we may not be able to identify down to the species level if the bug is in larval form. Metabarcoding is complementary to traditional methods in that it tells us DNA-level biodiversity, including species-level identification if the record is in the existing BOLD library. It can also distinguish how much variety exists within that taxon and/or between different sampling sites, thus giving more information on not only biodiversity but also biogeography.

A Firsthand Account

This summer I had the unique opportunity to work with SSI on a project to build a reference library for aquatic invertebrates. This reference library would provide us with a framework that would allow us to monitor how aquatic invertebrate communities change over time. As a recent graduate from UCSC (B.S. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology), I was both grateful and excited when I was offered this opportunity to work with SSI and Dave Herbst on this project. From the very first day of my internship the folks at SSI were extremely kind and welcoming. As an aspiring freshwater ecologist, it felt amazing to be surrounded by a group of scientists dedicated to furthering our understanding of watershed science.

We had so many awesome days in the field, and it astounded me how truly beautiful some of our stream sites were. Growing up in Southern California, I don’t think I had seen a “proper” river until my field work in the Sierras. When surveying sites like Oregon Creek, I sometimes just had to stop and take in the immense beauty of my surroundings. It really reassured me how much future work is needed to continue to protect our pristine rivers and help the native biota thrive under pressing anthropogenic stressors like climate change. It also reassured me how important organizations like SSI were for both protecting and restoring freshwater systems on a regional level. Having done some previous work with looking at aquatic invertebrate communities before, I knew the immense diversity of organisms that resides in rivers. However, after processing and sorting our many BMI samples, I started to really comprehend how much aquatic biodiversity lies in Sierra streams.

When it came to aquatic invertebrate taxonomy, I was in extremely good hands, considering I was working with Dave Herbst. Dave guided us and shared his immense knowledge with us on this project. Getting to work with SSI on this project was extremely rewarding. From sharing a cup of coffee in the office, to surveying streams together, I can say I truly enjoyed my time getting to know and work with the folks at SSI on this project. Although this project will eventually come to an end, I know my time and work on the western slopes of the Sierras is not done. I would like to thank SSI, Dave Herbst, and all my mentors for letting me be a part of this project.

-Ajith Seresinghe