We hope that the information on this page will not only increase your comfort level and knowledge of forest stewardship, fire, and treatment options to reduce the likelihood of high-severity fire on your property, but also introduce you to landscape-scale forest dynamics. As you navigate around this page we hope that you keep one primary philosophy in mind: there is no single right answer to the problem of fire in the Sierra foothills.

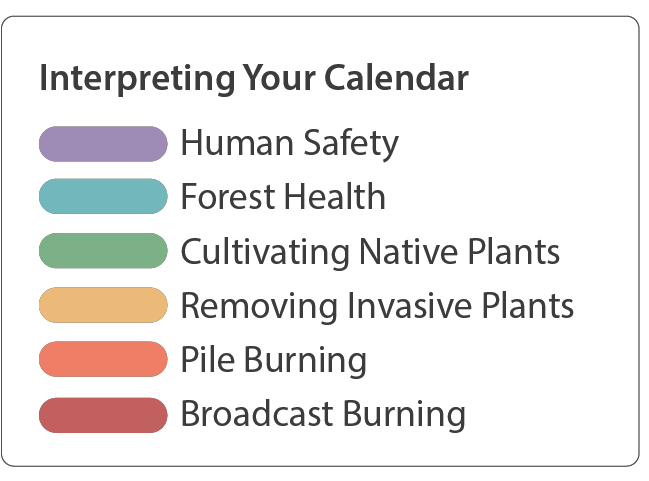

Land Stewardship Calendar

Techniques for responsible land management in the Northern Sierra Foothills

As residents of the wildland-urban interface (WUI), we have a responsibility to steward our lands to make them more resilient. This calendar was developed to inspire and remind residents of the ongoing stewardship actions that we can take. While the timelines

illustrated here may seem defined, the exact timing of each management activity is a suggested guideline and subject to change based on the present conditions. This is not a comprehensive list of all you can do to manage your lands; instead, it is a starting point to help cultivate a healthy, resilient ecosystem and be prepared for the eventuality of wildfire.

Resource Toolkit for Land Management in Western Nevada County

Statement of Purpose

Locally-Relevant Management Tips and Resources

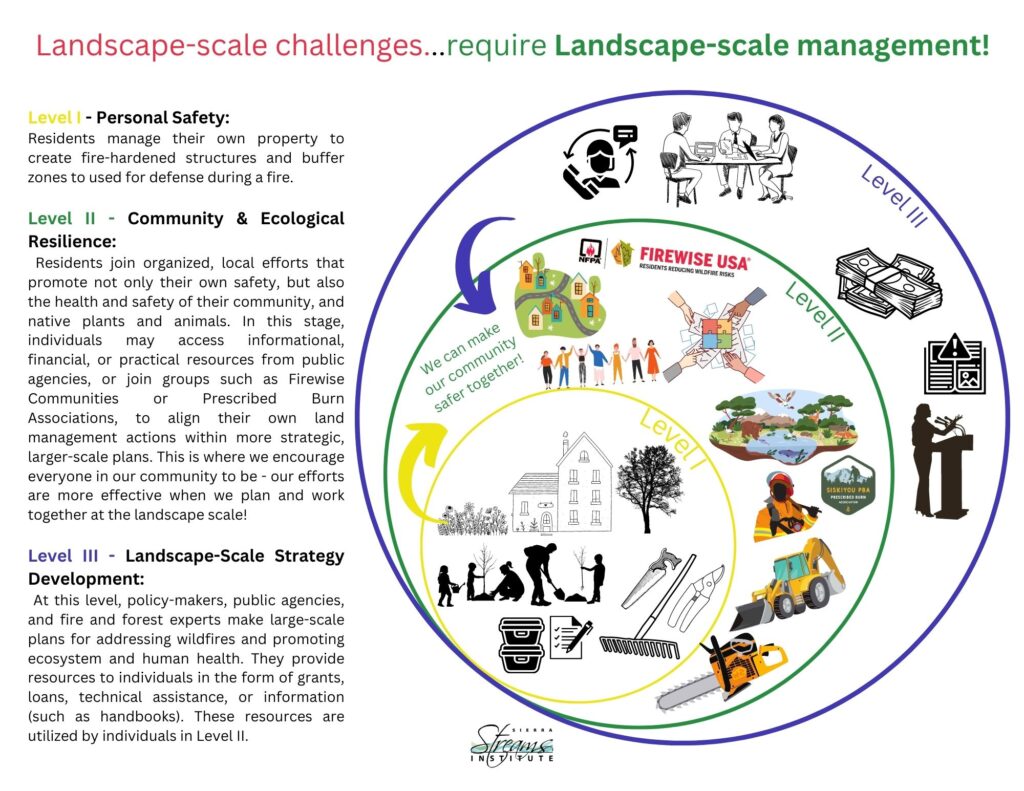

The Landscape Scale Management Approach

Forests and fire ignore property boundaries, and our approach to managing forest fuels should too.

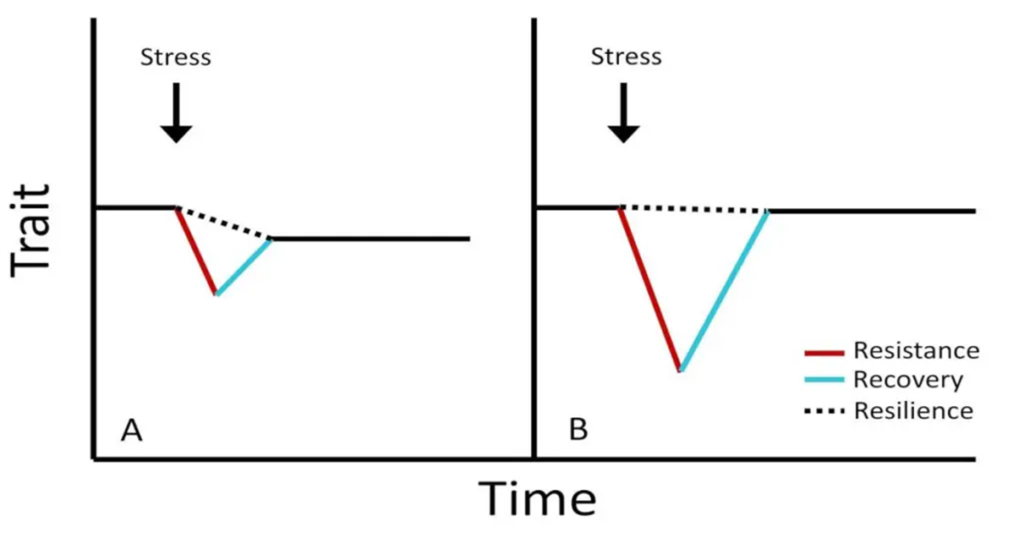

Heterogeneity and Resilience

“Resilience” is a term thrown around often in the world of environmental management. So what is resilience? Resilience is actually a measurable property of an organism or system, and is essentially “the inverse of resistance” divided by “recovery”. Resistance is an organism’s ability to withstand a stress, while recovery is its ability to return to pre-stress function.

Forest resilience is the ability of a forest stand or forested landscape to withstand stressors such as drought or fire and “recover”, with recovery being a function of everything from tree growth and health to overall forest ecosystem health such as diversity or wildlife habitat.

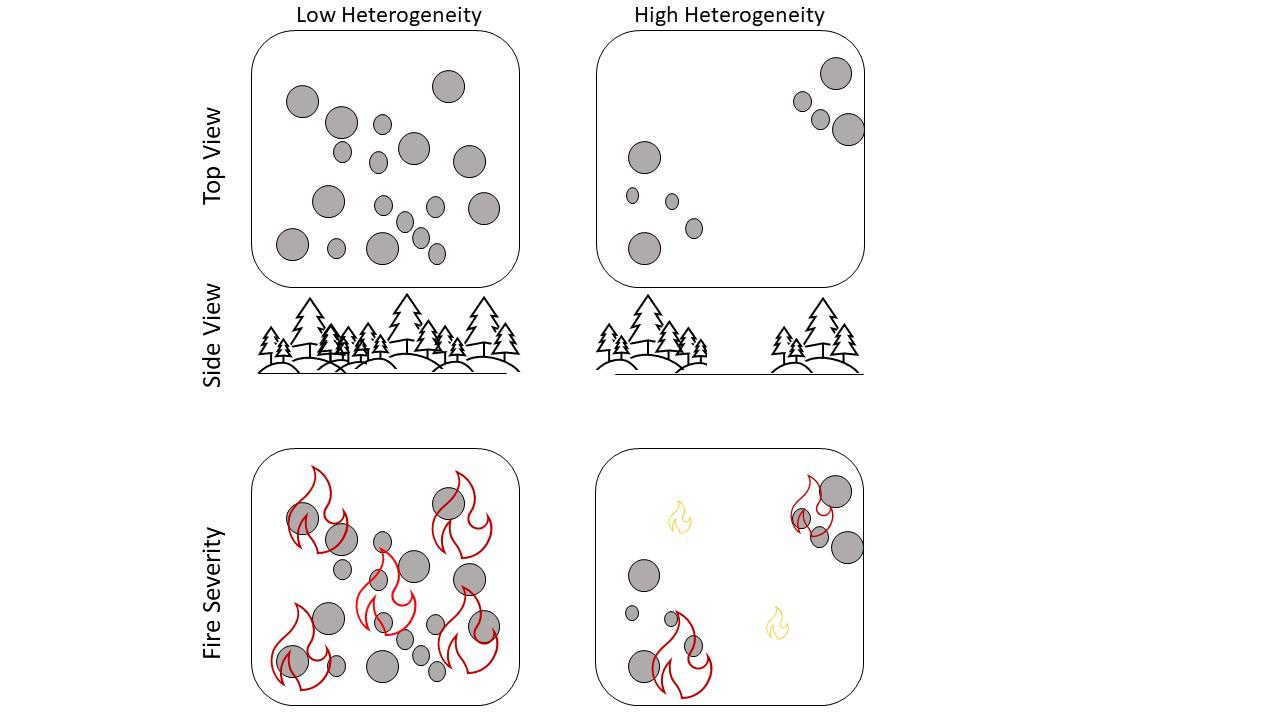

When it comes to wildfire, study after study continues to show that the most resilient forests are those with a high degree of “heterogeneity”—essentially “clumpiness”, or how variable a forest is in terms of its distribution of clumps and gaps. Forests with high levels of clumpiness mimic those that fires historically created, and that are fire-adapted. Fire can still burn hot in clumps of dense vegetation, but natural gaps where prior fires cleared vegetation act as breaks, slowing down fire spread and reducing overall landscape-scale fire severity.

Note that heterogeneity also does not just mean a lack of vegetation; remember that a forest without vegetation is no forest at all! Further, blanket treatments in which we only reduce shrubs or ladder fuels can reduce fire likelihood, but have some negative impacts we will discuss later in this document. Instead, creating gaps and leaving clumps mimics what forests that historically burned at low severity looked like, and these forests were (and can be) resilient.

How your property fits into the landscape

Your home in the WUI isn’t an island—it is a part of a connected forest landscape, and we should steward our properties with this in mind. This also means that in some cases, the best solution may be no work at all, as long as the forest is healthy in adjacent areas. Let’s consider your property and its place in the landscape as an extension of the defensible space model.

Find everything you need to know about defensible space on this website:

Defensible Space – Ready for Wildfire.

Resources for landscape-scale management

Planning at this scale isn’t always feasible or easy from our on-the-ground perspective within our own properties, but there are options for assistance.

FireWise Communities.

FireWise communities are groups of landowners that come together to get certified as a FireWise community. Certification requires management plans across the whole community, including work plans for fuel clearance, defensible space, and evacuation routes. Further, joining a FireWise community may help you reduce insurance costs!

For more information, and to identify a FireWise community near you, visit Firewise Communities – Ready for Wildfire.

Mapping options to view your landscape.

Using simple online tools can allow you to view your property at the landscape scale. Further, numerous tools exist for viewing your property in the context of landscape-scale fire.

Habitat Connectivity and Wildlife

Thinning ladder fuels and reducing overall forest density while considering heterogeneity will not only improve forest health and resilience to stressors, but develop habitat for wildlife. Forests of the Jones Bar area are overstocked with small-diameter biomass; with maintenance, this ensures protection of the forest component, and therefore, habitat and biodiversity protection.

Additional measures to improve habitat:

Incorporate brush piles

Brush piles offer perches for birds and cover for small animals. Brush piles should have the largest materials at the bottom, with the smallest-diameter brush at the top. Piles that are close to water are appealing to wildlife, and in openings where there is otherwise not much forest cover.

Retain snags

“Snags” are trees that are dead or dying. Snags are excellent for wildlife, as they offer cavities for nesting, limbs for perching, and numerous insects. “Choice” snags are trees that have cavities, loose bark, limbs, and signs of insect presence (holes, sawdust-like frass, galleries under bark). Different sizes and types of snags are encouraged.

Put up nest boxes

Nest boxes encourage nest sites for wildlife where they may otherwise not be present.

Exclude livestock from riparian areas

Using fencing to prevent browsing and trampling of soils and streams can restore vegetation, which provides cover and food for wildlife. Streams with shaded water are cooler and reduce evaporation which benefits aquatic species.

Promote habitat connectivity

Habitat connectivity refers to two or more areas of undeveloped habitat that are connected to each other in an otherwise isolated area. These areas are also referred to as “wildlife corridors”. These strips or patches of connectivity can attract wildlife and enable them to travel or dwell with a sense of safety.

Add water sources where feasible and protect pools

Incorporating bird baths or above/in-ground holding ponds are activities that support wildlife needs. Allow water to naturally pool and protect those pools from vehicles and heavy recreational use to limit erosion, maintain the water quality, and be a great source for drinking, resting or breeding—even if they are temporary.

Plant grasses, forbs, and trees

Herbaceous cover benefits many animals, including when the cover is in forest openings. Snakes, raptors, turkey, sparrows and foxes are some of the many animals that use these openings for hunting, feeding, and cover (Brittingham, 2016). Planting native bunchgrass is also a great idea. For example, deergrass (Muhlenbergia rigens) is easy to grow, and does well in almost any soil (Calscape, 2023). Native trees offer seed sources and cover that animals in the foothills are adapted to, and fruit trees attract numerous animals, including deer and bear (Brittingham, 2016).

Managing your forestland has the potential to greatly increase native species diversity and wildlife habitat. Removal of non-native invasive species such as Scotch broom and Himalayan blackberry and restoring habitat by planting, seeding, or utilizing the native seed bank that is there can restore forestland and attract more wildlife through higher plant diversity. Prescribed burning can also increase the diversity of forbs and grasses that emerge post-burn.

Oaks are particularly beneficial for wildlife, as their acorns are an excellent food source for insects, birds, rodents, deer, bear and other mammals. Numerous insect species use oak to complete their life cycles, such as gall wasps. Thinning while focusing on retaining oak trees on your property – prioritizing those that show promise in the years to come – can shape your land to support more wildlife. The Nature of Oaks: the Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees by Entomologist Douglas Tallamy (2021) is a wonderful book that highlights their importance through personal stories and science-based knowledge.

Observing areas where water tends to accumulate on your property can give you a sense for where water may be more available for vegetation in the future with our changing climate. These areas can be viewed as “climate refugia” sites, meaning zones of high relative water availability, which could be critical for drought-stressed sites now and under future climate change conditions (Mclaughlin et al. 2017). Thinning your property with a light touch on those sites to produce climate refugia “clumps” will more likely endure drought and serve as habitat in the future.

Bark Beetle

Tree diseases are common, varied, and often occur concomitantly. Diseases may be caused by biotic pathogens, including fungi. The mistletoe plant is a defoliator of trees (commonly oak), and insects can cause injury and potentially death. Drought, wind, smog, frost, flooding, high temperatures, fire and lightning cause tree damage, and the stress from these events can prompt attack by bark beetles.

Many bark beetles are native species, serving ecological roles: thinning forests, facilitating decomposition and are themselves food sources. However, dense stands coupled with drought can snowball into extensive bark beetle outbreaks. Generally, trees that are more spaced out are not competing as much for water and sunlight and are less stressed. Forest thinning as a preemptive management tool can limit bark beetle epidemics occurring on a landscape scale, limiting the range of the beetles if trees are vigorous and healthy.

There are hundreds of species of bark beetles found in the conifer forests of the West particular to different tree parts, from cones to tiny branches to the main stems of their hosts.

Common Beetles in the Sierra Nevada

Pine engraver beetle (Ips pini)

Credit: Ken Walker, Museum Victoria, Bugwood.org

Common in our area, and targets ponderosa pine, Jeffrey pine, limber pine and lodgepole pine. It attacks young pines up to 10 inches in diameter, but may attack larger trees during extreme drought and large-scale infestations.

Mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae)

Credit: Javier E. Mercado, Bark Beetle Genera of the U.S., USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org

Targets pines, including ponderosa, sugar, western white, coulter, and whitebark pines. It is the main insect pest of mature and overmature pine. Trees weakened by drought, lightning, fire, and wind are susceptible to this beetle, which has the potential to cause mass mortality events.

Western pine beetle (Dendroctonus brevicomis)

Credit: Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org

Hosts are Coulter pine and ponderosa pine. It is the most destructive insect pest of these pines in California.

Red turpentine beetle (Dendroctonus valens)

Credit: Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org

Targets all pines in California.

Douglas-fir beetle (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae)

Credit: Joseph Benzel, Screening Aids, USDA APHIS PPQ

Typically targets mature (>14” diameter) Douglas-fir trees, across most of the West. The beetles are drawn to and enter freshly cut or downed material.

Resources for Bark Beetle

University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources (UCANR) has a comprehensive website including identification and management of bark beetle infestations: Bark Beetles Management Guidelines–UC IPM. The rest of this section on bark beetle is excerpted from the UCANR. There is much more information on their website.

- Here is a link to a website that UCANR recommends, with images to help with beetle identification: Bark Beetles and Phloem Feeding Insects. (A few of these pages are printed out at the end of this binder.)

- This short video has incredible footage of bark beetle attack and pine resin defense, showing how beetles kill trees: It’s a Goopy Mess When Pines and Beetles Duke it Out

- U.S. Forest Service bark beetle fact sheet: Bark Beetles in California Conifers: Are Your Trees Susceptible?

- The California Forest Insect and Disease Training Manual from the U.S. Forest Service (comprehensive, includes beetles and beyond): California Forest Insect and Disease Training Manual

Damage and Signs

Bark beetles mine the inner bark (the phloem-cambial region) on twigs, branches, or trunks of trees and shrubs. This activity often starts a flow of tree resin in conifers, but sometimes even in hardwoods like elm and walnut. The resin flow (pitch tube) is accompanied by the sawdust-like frass created by the beetles. Frass accumulates in bark crevices or may drop and be visible on the ground or in spider webs. Small emergence holes in the bark are a good indication that bark beetles were present. Removal of the bark with the emergence holes often reveals dead and degraded inner bark and sometimes new adult beetles that have not yet emerged. Bark beetles frequently attack trees weakened by drought, disease, injuries, or other factors that may stress the tree. Bark beetles can contribute to the decline and eventual death of trees; however, only a few aggressive species are known to be the sole cause of tree mortality.

In addition to attacking larger limbs, some species such as cedar and cypress bark beetles feed by mining twigs up to 6 inches back from the end of the branch, resulting in dead tips. These discolored shoots hanging on the tree are often referred to as “flagging” or “flags.” Adult elm bark beetles feed on the inner bark of twigs before laying eggs. If an adult has emerged from cut logs or a portion of a tree that is infected by Dutch elm disease, the beetle’s body will be contaminated with fungal spores. When the adult beetle feeds on twigs, the beetle infects healthy elms with the fungi that cause Dutch elm disease. Elms showing yellowing or wilting branches in spring may be infected with Dutch elm disease and should be reported to the county agricultural commissioner.

Management

Except for general cultural practices that improve tree vigor, little can be done to control most bark beetles once trees have been attacked. Because the beetles live in the protected habitat beneath the bark, it is difficult to control them with insecticides. If trees or shrubs are infested, prune and dispose of bark beetle-infested limbs. If the main trunk is extensively attacked by bark beetles, the entire tree or shrub should be removed. Unless infested trees are cut and infested materials are quickly removed, burned, exposed to direct sunlight, or chipped on site, large numbers of beetles can emerge and kill nearby host trees, especially if live, unattacked trees nearby are weakened or stressed by other factors. Never pile infested material adjacent to a live tree or shrub. Preventative measures (below) are the best management tools to improve forest health and resilience to bark beetle attacks.

Before initiating any limb or tree removal with chainsaws, please be sure you’re practicing chainsaw safety. The Husqvarna company has a youtube channel with lots of good safety information, including personal protective equipment (PPE) and technique.

Cultural Control

Tree Selection

Forests are dynamic systems, and we shouldn’t feel a need to keep them exactly the way they are, but instead embrace natural change. This is important when considering tree species present now and what will be present in the future. For example, have you noticed that after fire or after thinning, more hardwood species (oaks, etc) come back than pines? This is a natural transition for our elevation. In some cases, planting conifers is appropriate, but in others, embrace that shift and the health of the natural trajectory of our mixed conifer/hardwood forest system.

Plant only species properly adapted to the area, while also considering future climate and pre-adaptation to expected conditions. Read the next section for more information on how to do that, and where to seek help. Learn the cultural requirements of trees, and provide proper care to keep them growing vigorously. Healthy trees are less likely to be attacked and are better able to survive attacks from a few bark beetles. Where bark beetles have been a problem, plant nonhost trees if possible, or ensure that planted trees have access to resources that allow them to flourish and not have weakened pest defenses. For instance, incense-cedars (Calocedrus decurrens) and oaks in our area rarely experience widespread mortality from bark beetles. A mixture of tree and shrub species in planted landscapes will reduce mortality resulting from bark beetles and wood borers.

Plant Sourcing

“Where are these seeds sourced from?” is an important question to ask at the nursery, or wherever you choose to source the trees from. Seed Zones were developed by CAL FIRE, and indicate areas of similar physiography (soil, elevation) and climate. Our seed zone is 525, as depicted in this Tree Seed Zone Map.

Sourcing plants grown with seed locally or within one’s seed zone has been a standard recommendation, to give the plants adapted to your area a better chance of success. But you would be right to think about climate change, and the success of your plantings based on projected drought and drier conditions.

Approaches to consider:

- Planting using seeds adapted to drier, hotter conditions originating from lower elevation may have greater success in respect to climate change (Young et al. 2020, North et al. 2018), and:

- Having different seed sources for a given species will promote genetic variation, which may benefit your future trees and forest to be more resilient to stressors.

Additional research supports planting not in the traditional rows, or “pines in lines”, format when we traditionally think about plantations, but, rather, in clumps with openings between them, emulating historic patterns and reducing potential fire severity (Larson and Churchill 2012, North et al. 2018).

In sum, different seed sources from further south or downslope could be a climate-smart choice. Variation is key! And, as always, forestry professionals are available to discuss these kinds of questions. They can also recommend species to plant that are appropriate for your soils, elevation, topography, and projected climate conditions.You may be eligible for financial assistance with procuring seedlings and planting labor through the nonprofit One Tree Planted. Contact: Brittney Burke (Brittney@onetreeplanted.org). Further financial resources and planning assistance can be provided by your local resource conservation district and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

Reduce Tree Stress

Pay particular attention to old, slow-growing trees, crowded groups of trees, and newly planted trees in the landscape. Large nursery stock or transplanted trees, notably oaks and pines, can become highly susceptible to bark beetles or wood borers after replanting. Transplanting success depends on the tree species and its condition, appropriate tree and site selection, characteristics of the planting site, the season of the year, the transplanting method, and follow-up care. Stresses placed on a tree caused by poor planting or planting at the wrong time of year, lack of proper care afterwards, or the planting of an inappropriate species for the site will increase a tree’s susceptibility to bark beetles or wood borers.

Prevention is the most effective method of managing bark beetles and related wood-boring insects; in most instances it is the only available control. Avoid injuries to roots and trunks, damage and soil compaction during construction activities, and protect trees from sunburn (sunscald) and other abiotic disorders. Irrigation may be important during dry summer months in drought years, especially with tree species that are native to regions where summer rain is common. Also, dense stands of susceptible trees should be thinned (complete removal of some of the trees) to increase the remaining trees’ vigor and ability to withstand an attack. High-value trees may be sprayed with insecticides to prevent beetle attacks. Consult with professionals for insecticide recommendations. Monitoring of the property on a regular basis will help spur mitigation activities.

Irrigate when appropriate around the outer canopy, not near the trunk. Avoid the frequent, shallow type of watering that is often used for lawns. A general recommendation is to irrigate trees infrequently, such as twice a month during drought periods. However, a sufficient amount of water must be used so that the water penetrates deeply into the soil (about 1 foot below the surface). The specific amount and frequency of water needed varies greatly depending on the site, size of the tree, and whether the tree species is adapted to summer drought or regular rainfall.

Prune infested limbs, and remove and dispose of dying trees so that bark- and wood-boring insects do not emerge and attack other nearby trees. Timing of pruning is important; avoid creating fresh pruning wounds during the adult beetles’ flight season. Do not prune elm trees from March to September or pines during February to mid-October.

Do not pile unseasoned, freshly cut wood near woody landscape plants. Freshly cut wood and trees that are dying or have recently died provide an abundant breeding source for some wood-boring beetles.

Tightly seal firewood beneath thick (10 mil), clear plastic sheets in a sunny location for several months to exclude attacking beetles, and kill any beetles already infesting the wood. To be effective, solar/plastic treatment requires vigilance and careful execution. It is important to keep wood piles small, use high-quality clear plastic resistant to UV (ultraviolet light) degradation, and thoroughly seal edges and promptly patch holes to prevent beetles from escaping.

For more information on cultural controls, see the publications by Donaldson and Seybold 1998 (PDF) and Sanborn 1996.

Biological Control

When bark beetles attack trees, natural enemies are attracted to feeding and mating bark beetles. The two main groups of natural enemies are predators and parasites. Predators are more important in regulating bark beetle populations than parasites. Natural enemies are unlikely to save an infested tree, but they can reduce bark beetle population size, thereby reducing the number of nearby trees that are attacked and killed by bark beetles. The release of predators and/or parasites into sites infested with bark beetles has not been an effective tactic to suppress bark beetle populations.

The following natural enemies attack the western pine beetle, but rarely control it: woodpeckers, several predaceous beetles such as the black-bellied clerid (Enoclerus lecontei) and a trogossitid beetle (Temnochila chlorodia), a predaceous fly (Medetera aldrichii), snakeflies, and parasitic wasps.

Credits, clockwise from top left: Erin Brady (audubon.org), Aaron Schusteff (bugguide.net), andesgascon_alex (iNaturalist Canada), UBC Zoology, tenebboy (bugguide.net).

Behavioral Control

Bark beetles locate mates and attract or repel other individuals of the same species by emitting species-specific airborne chemicals called pheromones. Pheromones are naturally occurring chemicals that are widely used as baits to monitor bark beetles by attracting them to traps. These baits are especially important for detecting invasive species. Professional foresters have sometimes controlled or suppressed small local populations of bark beetles by using attractant pheromones in traps, and repellent pheromones and other behavioral chemicals to deter beetles from valuable trees. Some behavioral chemicals are being used experimentally on an area-wide basis to protect stands of forest trees. The interactions among host trees and beetles and their pheromones are complex and often poorly understood. Researchers are refining the reliability of pheromone-based management techniques. Behavioral chemicals are currently recommended for use only by specially trained professionals familiar with bark beetle management. Landscape professionals and home gardeners should consult with local California Cooperative Extension specialists if they are interested in this management option.

For those with Douglas-fir trees, check out MCH Bubble Caps.

- From Forestry Suppliers: “Synergy Shield MCH Bubble Caps, Douglas-fir Beetle Repellent uses MCH – a naturally occurring anti-aggregation pheromone of the Douglas-fir beetle to protect trees from attack by Spruce, and Douglas-fir beetles.”

Blackberry Removal

Removal of invasive Himalayan blackberry must include removal of canes and roots in order to be effective.

Roots broken off in the soil during pulling and canes touching the ground can both resprout. Dig roots out when the soil is loose and moist rather than compacted and dry. Canes can also be cut after the plant flowers in the summer. Blackberry can regrow in loose, open soil even after you’ve completely removed existing plants. Areas where blackberry has been pulled should be replanted with natives, and revisited for several years to ensure there is no blackberry re-growth.

- Here is a video demonstration of blackberry removal by cutting away the canes and digging up the root wads: How to Remove Blackberries .

Blackberry roots and even canes that are touching the ground can re-root, so proper disposal is key. Oxbow Farm recommends collecting roots into a pile that one can keep an eye on while the roots dry out, and cutting and placing canes in a separate pile. Once they dry, they can be spread around as a spiky mulch. Adding them to your burn pile is also an option. Note that Waste Management in Nevada County does not accept blackberry!

More information about blackberry and removal from UCANR:

Wild Blackberries Management Guidelines–UC IPM.

Scotch Broom Removal

Like blackberry, Scotch broom will regrow from its roots. Roots can be very difficult to remove completely via pulling. Pulling also loosens the soil and opens up light for broom seeds, which remain viable for up to 80 years in the soil. Individual plants can produce up to 18,000 seeds, so there is a strong chance that they’re around. While young plants with small roots can be easily pulled in winter or spring, successive cuttings at ground level (and damage to any exposed roots) are more effective for mature plants. Cutting new growth at the base of the plant for two years in a row has anecdotally resulted in efficient removal.

What to do with cuttings? Above-ground cuttings can continue to mature even after they’ve been cut, resulting in the release of potentially thousands of seeds and new plant growth. Cuttings with buds, flowers and seeds need to be contained. Note that Waste Management in Nevada County does not accept Scotch broom. Cuttings can be burned.

- The group that produced the above video is Vancouver-based, but has excellent info that is useful for all kinds of broom management: BroomBusters

For chemical control of Scotch broom, see the “Chemical Control” section of this UCANR webpage: Brooms Management Guidelines–UC IPM.

Green Waste Disposal

Nevada County options: Green Waste Disposal | Nevada County, CA

Note that Waste Management does not accept the following as green waste:

- Branches more than 4 ft in length, 18 inches in diameter, or more than 50 lbs.

- Tree stumps

- Bamboo

- Soil or Dirt

- Diseased plants

- Concrete

- Blackberry

- Poison Oak

- Asphalt

- Plastic bags

- Animal Waste

- Palm tree branches

- Yucca plants

- Painted wood

- Treated wood

- Scotch Broom

- Cactus

Chipping and green waste resources may be available from the Fire Safe Council of Nevada County.

UCANR publication that includes “what to do with slash” on pg 7-8:

Forest Stewardship Series 15: Wildfire and Fuel Management.

UCANR forest stewardship assistance:

Forest Stewardship – Forest Research and Outreach.

Burn Piles

What you need to know from Cal Fire: Before you Burn – check this site to find out when it is safe and legal to burn!

Nevada County pile burning guidance: Manage Your Burn Pile Safely. Note that you cannot pile burn within Nevada City and Grass Valley city limits. If you live in another city, please check your local ordinances.

Check for workshops from UCANR, like this (past) one:

Pile Burning Workshop Webinar – Placer Resource Conservation District.

Placer Resource Conservation District regularly hosts online and in-person training events, particularly in the fall and winter months.

Broadcast Burning

Starting a controlled fire on the land for ecological and human benefit, also known as “prescribed fire”, is an excellent tool that landowners can use. The fire-adapted forests in California have been suppressed from fire for a very long time, resulting in the high-density, disease-prone forests that are seen today. Historically, fires burned every 8-20 years in the Sierra Nevada mixed conifer landscape. Clumps of trees, openings, and individual trees made up the spatial structure of the forests, which resulted largely from fire.

Benefits of prescribed fire include:

- fuels reduction

- control of species composition

- managing for biodiversity

- improved health of residual trees

- sequestration of carbon that could otherwise be lost to major wildfires

Careful planning and certain criteria must be met for burning to occur. Fuel moisture, weather, and smoke dispersal conditions are just a few. Prep work, a burn plan, appropriate permits and notifying the right people are the framework for a safe, successful burn. But it is possible, and you may find that the more you learn, the more you become an advocate yourself!

Where do I start?

Attend virtual and in-person training sessions! Attending prescribed burning workshops to learn how to plan, prepare, and burn on your property for little to no cost is extremely helpful.

Broadcast Burning Resources

Placer Resource Conservation District (RCD):

Prescribed Burning on Private Lands – Placer Resource Conservation District

Placer RCD has an email listserv that advertises in-person and online training events during the burn season. Contact the Prescribed Fire Program Manager, Cordi Craig, to be notified of future training events.

Prescribed Burn Associations (PBAs):

- PBAs are a coalition of volunteer landowners and others who partner to implement prescribed fire. They are separated into chapters, and our local chapter is called the Yuba Bear Burn Cooperative (YBBC), named for the watersheds. Attending events through YBBC during the burn season is an excellent way to gain experience learning to prep and conduct burns! They also have a gear trailer with everything needed to broadcast burn.

- Go to the YBBC website to get on their email listserv for future opportunities: https://calpba.org/yuba-bear-burn-cooperative

- YBBC planning resources are also available: https://calpba.org/rx-burn-planning

Prescribed Burning Permitting Questions:

- Jamie Jones, Executive Director of Nevada County FireSafe Council : jamie@areyoufiresafe.com

- Julie H, Air Pollution Control Specialist with Northern Sierra Air Management District: julieh@myairdistrict.com

- Joe, with Northern Sierra Air Management District (retiring December 2023): joef@myairdistrict.com

Contractors for Burning

There are contractors who will write burn plans for you, prep your property, and can do the burning itself.

Contact:

Volcano Creek Enterprises, Inc.

Amanda Godon

(530) 367-5629

P.O. Box 932, Foresthill, CA 95631

Prometheus Fire Consulting (Based in San Jose)

Info@PrometheusFireConsulting.com

(408) 807-1963

Funding and Technical Assistance Resources

Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP)

This USDA-run program applies to landowners (or renters) who manage land for agriculture or non-industrial private forest land.

- Minimum acreage: no

- Cost share: yes*

- Prescribed burning covered: yes

Factsheet: Is EQIP Right for Me?

Local NRCS Contacts:

- Evan Smith, Forester

Evan.t.smith@usda.gov - Valerie Bullard, Soil Conservationist

valerie.bullard@usda.gov

*Landowners must often pay up front, then will get reimbursed after the work is done. To apply, reach out to the local NRCS office and let them know you are interested. You will work with them to determine your eligibility.

California Forest Improvement Program (CFIP)

This program aims to improve forest resources, including animal habitat, and soil and water quality. Cost share is to hire a Registered Professional Forester to write a Forest Management Plan, and to oversee reforestation, stand improvement, and conservation practices/habitat improvement.

- Minimum acreage: 20 to 5,000 acres

- Cost share: yes*

- Prescribed burning covered: no

- CFIP User Guide

Contact:

- David Ahmadi, Forestry Assistance Specialist

David.Ahmadi@fire.ca.gov

143 B Spring Street

Grass Valley, CA 95945

*Funds get reimbursed after the work is completed. CFIP provides reimbursement at 75% or 90% cost share rates. Before filling out an application, consult with the Forestry Assistant Specialist, currently David Ahmadi (above).

Community Wildfire Defense Grant

This USDA Forest Service grant helps at-risk local communities and Tribes plan and reduce the risk against wildfire. The Act prioritizes at-risk communities in an area identified as having high or very high wildfire hazard potential, are low-income, and/or have been impacted by a severe disaster. Communities may develop the plans for project implementation.

For more information: Community Wildfire Defense Grant Program | US Forest Service.

Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program

This U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service program aims to restore habitats on working landscapes (e.g. forests, farms, ranches). This could involve improving water resources, planting native species, or oak woodland restoration. Their conservation priorities are wet meadows, streams and riparian habitats.

- Minimum acreage: No

- Cost share: 1:1 match, either cash and/or in-kind services

- Prescribed burning covered: In some instances; check with contact

- Website: Partners for Fish and Wildlife

Contact:

- Matt Hamman

matt_hamman@fws.gov

(530) 889-2301

11641 Blocker Drive, Suite 110

Auburn, CA 95603

California Vegetation Management Program (VMP)

This CAL FIRE program aims to reduce fuel loading to prevent catastrophic wildfire in California, with prescribed fire as a main focus.

The project area must be on State Responsibility Lands: SRA Viewer.

Note that as of early 2023, funding is not being offered. However, check their website for future opportunities.

Emergency Forest Restoration Program (EFRP)

This USDA-run program helps landowners of private forestland restore forest health that has been damaged by natural disasters. Drought or insect infestation do not apply. Debris removal, planting, fire lanes, fencing, wildlife enhancement are examples of work scopes.

- Minimum acreage: no

- Cost share: yes, up to 75% of the cost to implement practices can be provided.

- Prescribed burning covered: check with contact

Factsheet: Emergency Forest Restoration Progam (EFRP)

- Grass Valley Service Center

(530) 798-5527

113 Presley Way, Suite 1

Grass Valley, CA 95945

California Fire Safe Council Grants

This grant program emphasizes fire risk reduction activities by landowners and residents in at-risk communities to restore and maintain resilient landscapes and create fire-adapted communities. Individual landowners cannot apply—must have a legal fiscal sponsor. Check the website for current grant opportunities.

- Minimum acreage: may vary

- Cost share: 50/50 match required; cash, good, or in-kind services.

- Prescribed burning covered: yes

- Website: California Fire Safe Council

Other Potential Grant Sources

Nevada County Office of Emergency Services may offer FireWise Community grants on occasion.

Check their website for more information: Firewise Community Grants.

Navigating Permits

What is required for the type of forest management you want to do?

Check out this document from UCANR: Planning and Permitting Forest Fuel-Reduction Projects on Private Lands in CA – ANR Catalog (Page 4 includes a helpful flow chart).

Local Contractors

References

Agencies

CAL FIRE Forestry Assistance Specialists (FAS)

David Ahmadi – david.ahmadi@fire.ca.gov (El Dorado, Nevada, Placer, Sacramento, Sierra, Sutter, Tahoe Basin, Yuba Counties)

Nevada County Resource Conservation District – https://www.ncrcd.org/

Phone: (530) 272-3417, ext. 5529 or 5530

Monday-Friday 7:30am-4pm

113 Presley Way, Suite 1, Grass Valley, CA 95945

Placer County Resource Conservation District – https://placerrcd.org/

Phone: 530-390-6680

Email: info@placerrcd.org

Mailing Address: 11641 Blocker Dr. #120, Auburn, CA 95603

University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources – https://ucanr.edu/

UC Cooperative Extension Forest Advisors

Ricky Satomi (Sutter, Yuba, Butte, Nevada Counties)

Phone: (530) 822-6213

Email: rpsatomi@ucanr.edu

Rob York (Statewide)

(530) 333-4475

Email: ryork@berkeley.edu

Kristen Shive (Statewide)

Email: kshive@berkeley.edu

UC Cooperative Extension Placer and Nevada Counties – https://ceplacer.ucanr.edu/

Phone: (530) 273-4563

Email: cenevada@ucdavis.edu

Tuesday and Thursday, 8am-12pm and 12:30pm-4:30pm

255 South Auburn Street (Veterans Memorial Hall), Grass Valley, CA 95945

Text

Brittingham, M. (2016). Management practices for enhancing wildlife habitat. PennState Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/management-practices-for-enhancing-wildlife-habitat

Churchill, D. J., Larson, A. J., Dahlgreen, M. C., Franklin, J. F., Hessburg, P. F., & Lutz, J. A. (2013). Restoring forest resilience: From reference spatial patterns to silvicultural prescriptions and monitoring. Forest Ecology and Management, 291, 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.11.007

McLaughlin, B. C., Ackerly, D. D., Klos, P. Z., Natali, J., Dawson, T. E., & Thompson, S. E. (2017). Hydrologic refugia, plants, and climate change. Global Change Biology, 23(8), 2941–2961.

North, M. P., Stevens, J. T., Greene, D. F., Coppoletta, M., Knapp, E. E., Latimer, A. M., Restaino, C. M., Tompkins, R. E., Welch, K. R., York, R. A., Young, D. J. N., Axelson, J. N., Buckley, T. N., Estes, B. L., Hager, R. N., Long, J. W., Meyer, M. D., Ostoja, S. M., Safford, H. D., … Wyrsch, P. (2019). Tamm Review: Reforestation for resilience in dry western U.S. forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 432, 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.09.007

Stine, Peter A.; Ostoja, Steven M.; McMorrow, Stewart. 2021. Forest management handbook for small-parcel landowners in the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascade Range. Info. Fore.

PSW-INF-1. Albany, CA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific

Southwest Research Station. 85 p. PDF available here: https://www.ncrcd.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Forest-Management-for-Small-Parcels.pdf

U.S. Forest Service, Region 5, Forest Health Protection and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, Forest Pest Management forest health specialists. 2015. California Forest Insect and Disease Training Manual. 2015

Young, D. J. N., Meyer, M., Estes, B., Gross, S., Wuenschel, A., Restaino, C., & Safford, H. D. (2020). Forest recovery following extreme drought in California, USA: Natural patterns and effects of pre‐drought management. Ecological Applications, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2002

Created with funding from California Wildlife Conservation Board