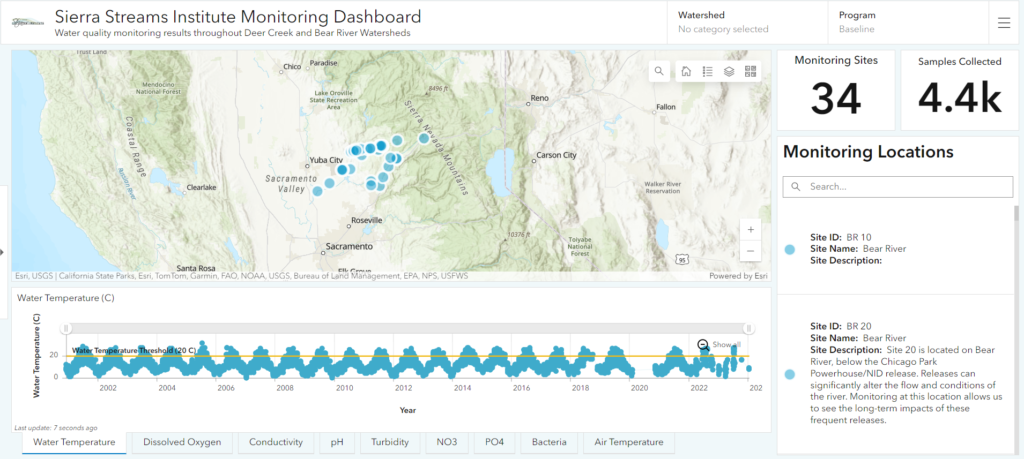

Sierra Streams Institute works with community members to monitor the health of Deer Creek, our home watershed, as well as the Bear River. Collecting these data regularly over time allows us to see changes, evaluate restoration efforts, and locate sources of potential problems.

Our quarterly baseline monitoring collects data on water temperature, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, pH, and turbidity; these “vital signs” tell us how the creek is doing and what kinds of life can inhabit its waters. We also check nutrient and bacteria levels, which are important for algae growth and safe swimming.

Our targeted monitoring collects the same baseline parameters, but our volunteers go out specifically during winter storms and the hottest part of the summer. By seeing how the creek is doing at these “extreme” times, we have a better understanding of creek conditions year-round.

Our annual creek surveys are an in-depth collection of data on benthic macroinvertebrates (BMI), algae, and the physical habitat of the creek. This is an important addition to our data on water chemistry (temperature, pH etc.) because it gives us direct information on what lives in the creek and the nitty gritty on what the creek looks like.

Together, knowing the trends in water chemistry over time as well as the BMI and algae that a creek supports gives us an understanding of the creek ecosystem as a whole. We can then take into account large scale factors such as drought and wildfire, and determine the success of riparian restoration projects. Everything in a watershed is connected, from the headwaters all the way downstream, and it’s connected by water.

What is a watershed?

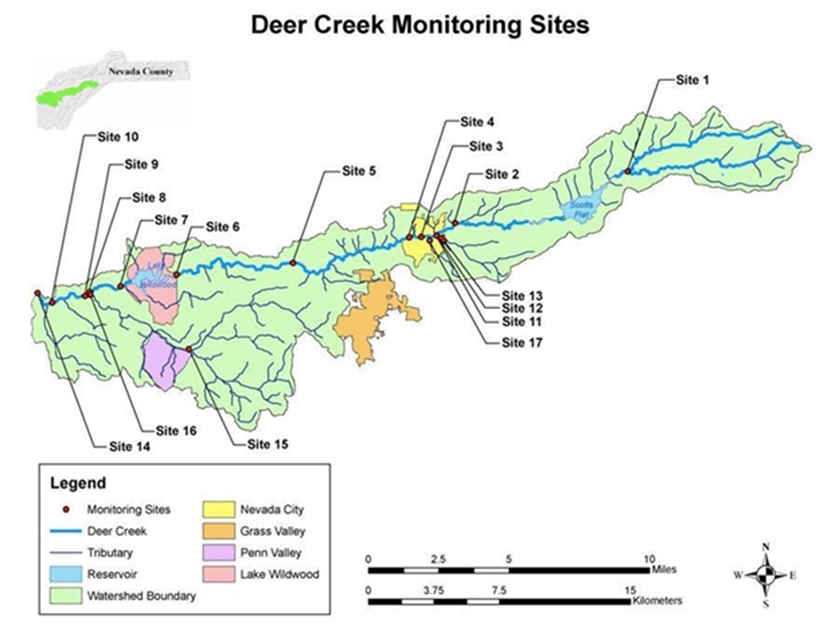

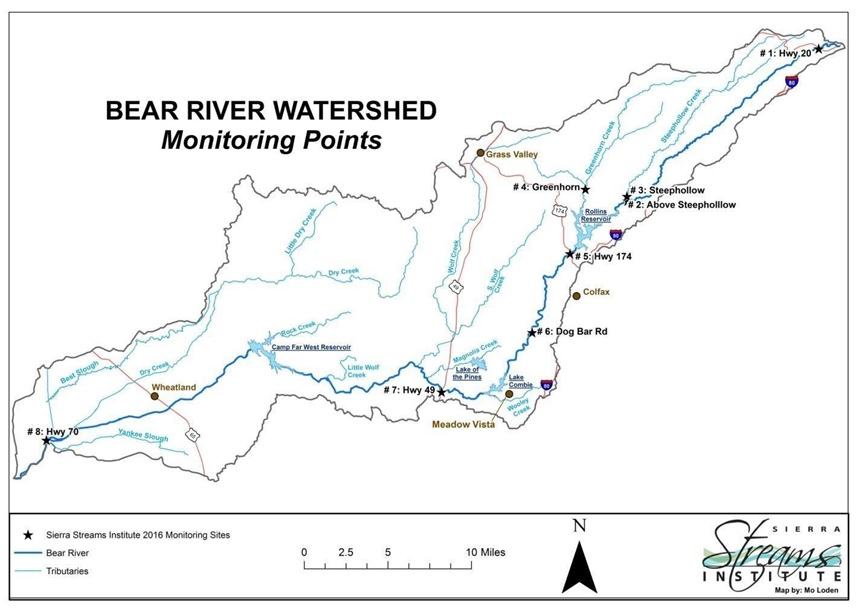

A watershed is an area of land where, when it rains, all the water flows downhill to the same place. All the land that drains to Deer Creek is the Deer Creek Watershed. Deer Creek eventually flows into the Yuba River. All the land that drains to the Yuba River is the Yuba River Watershed, which includes the Deer Creek Watershed. Below are maps of the Deer Creek Watershed and Bear River Watershed, including SSI’s monitoring sites.

What do we measure?

Vital Signs

Our water quality monitors collect data on certain “vital signs,” which tell us how the creek is doing and what kinds of life can inhabit its waters:

Dissolved Oxygen

Aquatic organisms depend on oxygen for respiration. Oxygen is dissolved in water through aeration (via moving over rocks or waterfalls) and photosynthesis (by plants living in the creek). Cold water can hold more dissolved oxygen than warm water, because the molecules in the water move slower and less dissolved gas is lost.

At least 5mg/L (milligrams per liter) of dissolved oxygen is necessary for supporting aquatic life, and above 8mg/L is preferred by most species.

Specific Conductivity

Conductivity measures the concentration of any charged particles present in water; this could be in the form of salts, nutrients like nitrates or phosphates, or any other ions. Conductivity may be related to the underlying geology of the stream bed, or come from urban runoff containing things like fertilizers. Because ions can move faster in warmer water (it is less viscous), the conductivity of water increases with rising temperature. We compensate our readings to a standard temperature to minimize this effect, and refer to it as specific conductivity.

Generally it is easier for creek critters to live with lower conductivity, although it depends because conductivity can be such a wide variety of things, some of which are necessary to aquatic life in small amounts.

Turbidity

Turbidity refers to the clarity of the water, with low turbidity indicating clearer, healthier water. Sediment or dissolved solids in the water can stick in the gills of fish, settle on top of fish eggs, and even impair fish’s vision in their hunt for food. Filter-feeding invertebrates can also become clogged with sediments, leading to starvation. Because solids heat up faster than water, high levels of solid material in water can increase the temperature of the water, which leads to lower oxygen levels (see dissolved oxygen section).

Rainfall often increases turbidity in creeks for a short time, as stormwater runoff contributes to higher flows and can cause creek-bed and watershed-scale erosion. Other sources of increased turbidity include algal blooms, waste discharge, and even animals or children playing in the water.

Fish prefer very clear water, with a turbidity of less than 10 FAU (Formazin Attenuation Units).

Temperature

Water temperature affects all creatures living in the stream, as well as directly influencing water chemistry (see conductivity and dissolved oxygen sections). Deep, fast-moving, and shaded streams tend to be colder than shallow, slow-moving, and exposed streams.

Different animals have different preferred temperature ranges; cold water fish such as rainbow trout like water to be less than 16 degrees Celsius, although they can tolerate higher temperatures.

pH

pH is a measure of how acidic or basic the water is. pH in streams can be affected by many things, including urban runoff, mining activities, and even pine needles. Typically, the presence of organic matter and decomposition decrease pH, making the water more acidic, while urban runoff tends to increase pH.

A pH range of 6.5 to 8.5 is optimal for the health of freshwater fish and bottom-dwelling macroinvertebrates.

Nutrients/Bacteria

Our monitors also check nutrient and bacteria levels, which are important for algae growth and safe swimming.

E. coli as a fecal indicator bacteria

E. coli is found in the feces of warm blooded animals including humans, and is used as an indicator bacteria, meaning that it is both easy to test for and also tends to be present when other, more harmful bacteria and microorganisms are present. (Some strains of E. coli are harmful, but most are non-pathogenic and live harmlessly, in fact helpfully, in our bodies.) Sources of E. coli include animal and human waste, and tend to be more concentrated in urban areas, where we have more sewage leaks, dog parks, etc. When levels of the indicator bacteria E. coli are high it means that people (especially small children and the elderly) should avoid contact with the water. The EPA has established safe thresholds for E. coli in recreational waters, and we compare our findings with those thresholds to determine if certain areas should be closed to creek access temporarily.

Every summer in the creeks, as the temperature increases and water flow decreases, we see an increase in bacteria at many of our monitoring sites. Some amount of bacteria is always present in creek water, but less water in the creek concentrates any bacteria present, and higher temperatures increase the amount of time bacteria can live in the water, and even multiply.

Nutrients

Nutrients are essential for life in a creek, but in excess, they can lead to overgrowth of algae and ultimately low oxygen conditions and “dead zones” (see section on eutrophication).

Nitrates (N03–) are formed from the element nitrogen. Sources of nitrates include fertilizer, animal waste, human waste (often from leaking septic systems or overloaded wastewater treatment systems), and industrial pollution. Nitrates are a critical nutrient for aquatic plants and algae, which need nitrates to grow. However, high levels of nitrates can lead to overgrowth of algae and eutrophication (areas where there is little or no oxygen in the water).

Phosphates (PO43-) are formed from the element phosphorus. Phosphates are an important nutrient for aquatic plants and algae, but similar to nitrates, too much can lead to unchecked growth and low oxygen conditions. Sources of phosphates include urban landscape runoff such as fertilizer and detergents, as well as human and animal waste.

Creek Surveys

We also do annual creek surveys, where we collect detailed information on what lives in the creeks and the physical habitat of the creek.

Benthic Macroinvertebrates (BMI) are small animals living at the bottom (benthos) of streams, including many insects that spend part or all of their life in the creek. They are large enough to see with the naked eye (macro) and have no backbone (invertebrate). Because BMI live in a variety of habitats and have a range of tolerance levels to pollution, they act as excellent indicators of stream health. Looking at the BMI that live in a creek allows us to evaluate long-term trends in watershed health, rather than the momentary snapshot in time that we get from measuring temperature or dissolved oxygen quarterly. For example, stoneflies have a very low tolerance for pollutants, so if the creek supports a thriving stonefly population, water quality must have been good for some time.

Algae are a diverse group of plant-like organisms that live in water. Like plants, they produce oxygen through photosynthesis. They need nutrients to grow, and are an important part of the food chain in creeks, but overgrowth can lead to problems like eutrophication (see next section for more information).

The physical habitat of a creek includes how wide it is, how deep it is, how much it curves, how much water moves through it, and what the surrounding area looks like – are there lots of trees and shrubs? Are there a lot of roads and bridges? The answers to these questions provide important information about what it’s like to live in the creek, and can also help us track how the creek changes over time.

What is eutrophication?

Eutrophication works like this: when nutrient levels are high, algae will grow and grow until the water is visibly green, preventing light from penetrating very far. The increased amount of algae (which acts as a solid in the water) increases the water temperature. When the nutrients in the water have been used up, or when the sun goes down, the algae stop growing and become a major source of food for bacteria. Bacteria then grow and grow, eating algae and using up oxygen. This creates such a low-oxygen environment that many invertebrates and fish can’t survive. Bacterial metabolism also releases ions into the water that increase conductivity and reduce pH. Whether it’s a daily fluctuation or a one-time oxygen crash, eutrophication can make it impossible for the creek to support most life.

When do we monitor?

Baseline monitoring

Our quarterly monitoring looks at all of the above parameters (the vitals like temperature, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, conductivity, and pH, as well as bacteria and nutrients) to get an idea of what the creek looks like over many years. We have been monitoring Deer Creek for over 20 years now, and we have a good baseline understanding of what it is like in wet years and dry years. We have been monitoring Bear River since 2016. Volunteers monitor our sites in both watersheds every January, April, July, and October.

Targeted monitoring

Now that we have this baseline, we are interested in the extremes: What is the creek like during a winter storm? What is it like in the late summer, when it is at its hottest and driest? Starting in 2022, teams of volunteers have been going out to collect all our normal parameters during these extreme times so that we can have a better understanding of the creek at all times of the year, and how things might change with increasing climate variability.

Creek surveys

In June and October, we do in-depth surveys of algae and benthic macroinvertebrates (BMI) in certain sections of the creek. Additionally, in June we do a full survey of the physical habitat of the creek and surrounding riparian area.

We train community volunteers to help us with all these aspects of monitoring the health of the creek! Learn more here.

What can you do?

Humans tend to cause some problems for the healthy function of watersheds. We pave over large sections of ground, which then build up pollutants during the dry season and deliver these pollutants directly to creeks when it rains via gutters and storm drains; paved areas also reduce the amount of water that can filter through the soil and reach the groundwater when it rains. We build homes near creeks, which can be a potential source of soil erosion and household chemicals and fertilizers when it rains. We need to treat our sewage, but then we discharge that treated water to the creek, which often contains much higher levels of nutrients than is natural for a creek. Farms can contribute fertilizers and pesticides to nearby creeks, and also harm the vegetation on the creekbank. Dams help us get reliable sources of drinking water, but they interrupt the natural flow of the water and impact water quality and fish migration.

While we can’t remove these problems, we can minimize their impacts by adopting “creek-friendly” practices. Think about what might reach the nearest waterway via a gutter or storm drain, and act accordingly when you apply fertilizer to your garden. Support permeable paving projects in your community. Consider biking or walking rather than driving for short trips. Visitors, homeowners, developers, water management agencies, city, county, and state stakeholder agencies, farmers and ranchers, and local businesses all have a role to play in keeping their watershed healthy.

Click Here to See Our Monitoring Data Dashboard